Previously: Prologue

In the 19th Century, political parties still followed the British tradition of having caucus select their leader. At least, they followed this tradition when they felt the need to have a leader. In both the 1867 and 1872 elections, the Liberals ran sans chef. That may seem unfathomable today, but all politics was local in those days – a look at the results of the 1867 election shows many candidates won with only a few hundred votes, and the winner was actually acclaimed in over 40 ridings. The parties themselves had been evolving for decades, and looked more like a mish-mash of like-minded factions than the leadership vehicles they are today.

That said, after coming within 5 seats of winning the 1872 election, the Liberals recognized the time had come to name a leader.

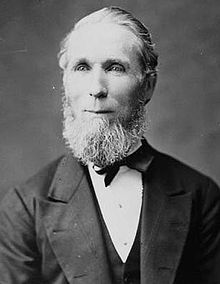

That Alexander Mackenzie would be that leader is somewhat surprising, when you consider his background. He had come to Canada from Scotland at the age of 20 as a stonecutter, and in the words of George Bowering:

“He was diligent and honest, and he was not a lawyer. Despite all these drawbacks, he rose steadily through the political ranks.”

True to form, when the time came to pick a leader, Mackenzie was reluctant to take on the title. He suggested the party look to George Brown…or Edward Blake…or Luther Hamilton Holton…or Antoine-Aimé Dorion…or anyone else. One by one, they all declined (though Blake, in true Liberal fashion, would try to oust Mackenzie two years later).

Even though Mackenzie may not have been Mackenzie’s first choice, he was likely the man caucus wanted. He had assumed many of the traditional “leader” responsibilities in the House following Brown’s retirement in 1867 and, with Blake sick for much of the 1872 campaign, had taken on a leadership role during that election, campaigning in nearly 20 Ontario constituencies. Mackenzie was not just the “default choice” who assumed the post because no one else wanted it – he had the necessary resume and experience, and likely would have won a contested vote had there been more interest in the job.

Sure enough, Mackenzie performed well enough in government after riding MacDonald’s Pacific Scandal to power. I won’t dwell on his time as Prime Minister, since this blog series is about how these men became leaders, but Mackenkie reshaped the way the country was run, introducing the secret ballot, single-day elections, the Auditor General’s office, and the Supreme Court.

Mackenzie stayed true to his humble origins, turning down the Queen’s offer of a knighthood on three separate occasions. He was as honest a politician as you could find in the 19th century – perhaps in our country’s history.

So, of course, he was doomed to failure. Which is why five MPs (including a young Wilfrid Laurier) came knocking on Mackenzie’s door in 1880, to inform him he had been replaced with…

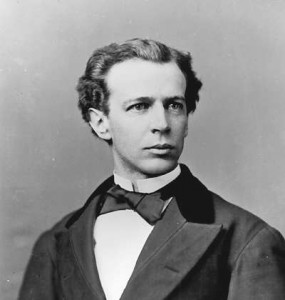

Edward Blake has been remembered by history as “that Liberal who never became Prime Minister”. Which is unfair to a man who founded one of Canada’s largest law firms, served as Premier of Ontario, was chancellor of the University of Toronto, and was elected to both the Canadian and British Houses of Commons.

Unlike Mackenzie, Blake came straight out of the politician mould, so it’s not difficult to chart how his career path led to the party leadership. His father was a politician, and Edward was educated at Upper Canada College and the University of Toronto. He was recruited into politics by George Brown and found himself leader of the Ontario Liberal Party by the age of 35. Blake jumped to federal politics in 1872 and likely would have been the first Liberal Prime Minister instead of Mackenzie, if health problems and the death of his infant daughter hadn’t prompted him to take a pass when the time came to choose the party’s first leader.

Blake clearly had ambitions, and he kindly offered to take over the Prime Minister’s job from Mackenzie when he returned to health. When Mackenzie gave him a “thanks but no thanks” reply, Blake made some less kind speeches snidely critiquing his leader.

Despite this (or perhaps because of it), Mackenzie convinced Blake to re-enter the Cabinet in 1875, as Minister of Justice, where he served for two years before health issues again forced him out of politics.

By 1880, the Liberals were in opposition, and caucus was getting antsy, so – stop me if you’ve heard this story before – they forced out Mackenzie in favour of Blake.

Blake was the obvious choice given his experience and profile, and there weren’t really any alternatives by this point – Brown and Holton had died earlier that year, and Wilfrid Laurier was still too young and too French for the job.

However, 7 years later, Laurier was 7 years older, and the Louis Riel hanging suddenly made “the French thing” less of a liability.

It’s easy to forget that those living through history don’t have the opportunity to read ahead. We get few advanced warnings for greatness. Pierre Trudeau was only crowned Liberal leader on the 4th ballot. William Lyon Mackenzie King won by 38 votes on the 5th ballot. So just because Wilfrid Laurier went on to become one of the most successful leaders in Canadian history, we shouldn’t assume everyone saw it coming in 1887. In fact, few did.

It’s not that greatness was never expected of Laurier. He had always been a rising star – that first round draft pick you pin your hopes on. He had been elected provincially at the age of 30, and had jumped federally three years later. In 1877, he became a household name after delivering a powerful speech to 2,000 listeners in Quebec City’s Salle de Musique, dispelling the belief that being a Liberal was akin to heresy (a belief still shared by most at Sun News). Later that year, as a result of Laurier’s speech (and a nudge from the Vatican), Quebec bishops issued a decree that no political party was to be condemned. Laurier had become a star, and would soon be elevated to Cabinet as the Liberal Party’s voice – and chief organizer – in Quebec.

Despite this early promise, Laurier’s development stalled on the opposition benches, during Blake’s leadership. Like a lot of first round picks, Laurier was starting to look more and more like a bust. He appeared “lazy” and “uninterested” in the House, prompting journalist JW Dafoe to write the following in 1884:

“He was then in his forty-third year; but in the judgment of many his career was over. […] There were memories in the House of Laurier’s eloquence, but memories only.”

So when Blake resigned in 1887, once again due to poor health, Laurier was not the obvious successor. In his book on Laurier, Andre Pratte remarks “had there been a spontaneous vote among the members of the Liberal caucus, Laurier would certainly not have been at the top of the list of potential successors.” While Laurier had scored points and raised his profile in Quebec after the Riel execution, many were skeptical Ontarians would ever vote for a French Canadian Catholic. Even Laurier himself was doubtful, begging Blake to stay, telling his mentor “there is no one to take your place”.

But here is where Edward Blake, despite his flaws and failings, deserves to go down in history as one of the titans of the Liberal Party. Although prominent Ontario Liberals Richard Cartwright and David Mills expressed interest in Blake’s job, and likely had more support within caucus, Blake put down his foot and insisted on Laurier. The outgoing leader first talked Laurier into accepting his job, then talked the caucus into backing his reluctant protégé. In the end, it became a formality with Cartwright nominating and Mills seconding Laurier for the leadership post, but only because Blake had used every last drop of political capital to whip caucus in line behind his chosen successor.

The next day, La Minerve newspaper responded with the hilarious-with-hindsight assessment of the choice as “replacing a giant by a pygmy”. It would take a few elections to prove the skeptics wrong, but thanks to Blake, Laurier would go down in history as the tallest giant in the party’s history.

For More Information:

Alexander Mackenzie Parliamentary Biography

Library of Canada – Alexander Mackenzie

The Canadian Encyclopedia – Edward Blake

Canadian Biography – Edward Blake

Canadian Biography – Wilfrid Laurier

George Bowering’s very awesome book, Egotists and Autocrats

Barbara Robertson’s Sir Wilfrid Laurier: The Great Conciliator

Martin Spigelman’s Wilfrid Laurier

Andre Pratte’s Extraordinary Canadians: Wilfrid Laurier

2 responses to “Liberal Leadership Races Through History (Part 1): The 19th Century”

Excellent work Dan. Very fun to read a summary of this history. Looking forward to each of the subsequent parts.

[…] 2): An Elected King Posted at 12:15 on September 24, 2012 by calgarygrit Previously: Prologue, The 19th Century Spoiler Alert: He sees dead people…or at least, got advice from them. In 2… This entry […]